Film Review; The Dawn Wall.

An awe-inspiring documentary puts you on the surface of the world’s most forbidding rock face, along with daredevil climbers Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson, as we relive the 2015 free climb that made history.

….. by Owen Gleiberman of Variety Magazine 2018

Later this year — starting, perhaps, with the release of “First Man,” Damien Chazelle’s epic biographical drama about Neil Armstrong and the space program — America will commence what promises to be a momentous and meditative celebration of the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing. What will be celebrated, of course, isn’t just the immensity of the achievement. It will be the spirit that the moon landing still symbolizes: the idea that human beings — and, yes, Americans — could once imagine doing almost anything, and then just go out and do it. That we could realize the impossible dream.

Simplistic or not, that’s the way we now think of the America of 50 years ago, as a society of majestic striving. But it’s not as though that spirit has disappeared. You could argue that it’s still all around us, entangled in murkier forces — the we-can-do-anything dream buried under the rancor of our current divisiveness.

If you want to catch an awe-inspiring glimpse of what that spirit still looks like, not as late-’60s lunar-walk nostalgia but in a contemporary form that’s as pure and heady as a hit of oxygen, look no further than “The Dawn Wall.” It’s a riveting and spectacular documentary about Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson, the two American rock climbers who accomplished the most extraordinary feat of free climbing in history. In January 2015, over the course of 19 days, they scaled the legendary Dawn Wall section of El Capitan, the ominously vertical rock formation in Yosemite National Park — a famously forbidding 3,000-foot granite monolith of minimal juts and crags, the kind of surface it would be hard to imagine anyone wriggling to the top of who wasn’t Spider-Man.

“The Dawn Wall” immerses us in every dimension of their achievement: the athleticism, the drop-dead audacity, the complex human drama. But the first thing to say about the movie, and what makes it a must-see experience, is that for the entire climb we’re right there, on the surface of the rock, along with Caldwell and Jorgeson. The film’s co-directors, Josh Lowell and Peter Mortimer, are climbers themselves who have helmed a number of entries in the “Reel Rock” film series, and working with a team of cinematographers led by Brett Lowell, they stationed bodies and cameras up on the Dawn Wall, dangling from lines tethered to the top, so that Caldwell and Jorgeson’s vertiginous, bewildering, up-in-the-air journey becomes ours.

The camera places us inches from their lime-braised and often bloodied fingers, as they grasp for the tiniest of razor-sharp ridges (which slice layers of skin off their fingertips), hoisting themselves up what is basically a polished sheet of rock. We’re there when they fall, plunging straight down before they’re caught and held by safety lines — a ritual that gave someone like me, who isn’t even comfortable looking out of tall buildings, a heart-in-the-throat moment each time, since all I could think was, “Okay, I get it, the safety line is hammered into a wedge up above. But what if it comes loose?”

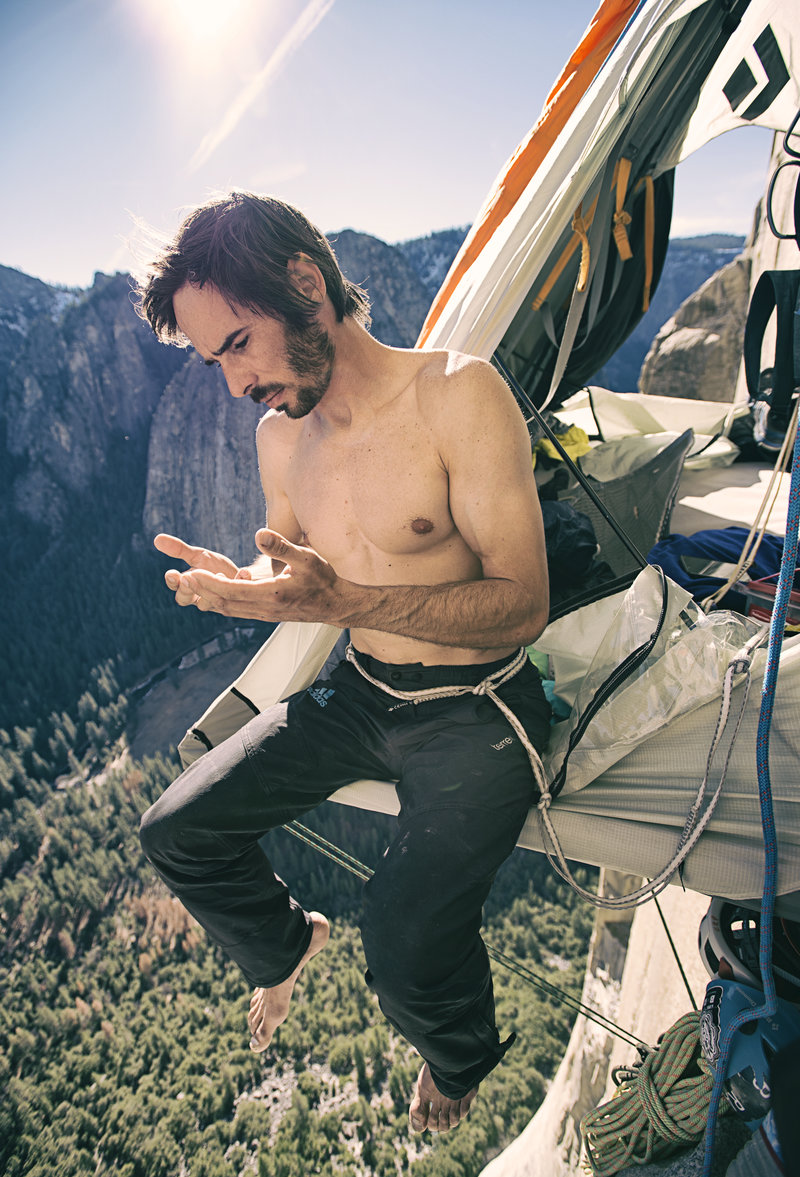

We’re there when the two camp out each night, in a tent that’s improbably but securely fastened to the side of the rock face; there, they sleep, talk, drink coffee and water, and speak to journalists on their cell phones. One call, out of nowhere, from reporter John Branch results in the front-page New York Times story that, overnight, elevated the climb from an eccentric and relatively low-profile adventure, tracked mostly by rock-climbing cultists, into an international media event.

At the time, the story was all about bravado and perseverance and dizzying heights. It’s still about those things, but experienced this close up, it’s also about the tactility — and spirituality — of pain and endurance. The pain, which might be standard in any portrait of extreme athletics, seems to fulfill something in the karma of Tommy Caldwell. He was 36 years old when he led this climb, and he’d been working up to it for a decade, scaling dozens of sections of the Dawn Wall, devising strategies and techniques, all the while contemplating whether the feat was even possible.

Tommy, good-looking in a rabbit-toothed way, with a disarmingly gentle manner, comes off as a complete contradiction; he’s like Mike White reborn as a fearless jock. Born and raised near the Colorado Rockies, Tommy grew up the son of a bodybuilder and began to climb when he was very young, but his grade-school teachers thought there was something developmentally wrong with him. Even when he finds his identity as a teenage scaler of stone surfaces, he’s thought of as a kind of climbing savant. He’ll shimmy up any rock face you can find, hovering thousands of feet above ground, and up there — maybe only up there — he feels at home.

Disaster has a way of breaking out around Tommy. In 2000, he and Beth Rodden, the free climber who became his soulmate and wife for seven years, travel, along with a team of climbing partners, to Kyrgyzstan to scale the famous peaks there. But once in the country they’re taken hostage by armed rebels at war with the Kyrgyz government. After being paraded through the mountains as prisoners, Tommy decides that the only way he can save their lives is to shove one of the kidnappers off a ledge, which he does, an act that leaves him in paroxysms of guilt.

Back home, after he and Beth are married, he’s doing renovations with a table saw when he slices off the top half of his left index finger — an injury that would devastate anyone. In this case, it seemed destined to destroy Tommy’s athletic career, since when scaling vertical rocks your index fingers are the two main tools you have. But Tommy trains his other fingers (and his index stub) to do the same work, turning the liability into a toughening advantage. Then his marriage ends, crushing him. (Beth Rodden, interviewed in the film, traces the seed of its dissolution to the kidnapping.) Only then does he summon the fortitude to scale the Dawn Wall.

The movie sketches in the sources of his climbing zeal, but Tommy Caldwell remains one of those inexplicable originals. “The Dawn Wall,” in capturing the insanity of fervor that drove him to undertake the ultimate feat of climbing, is a high-strung daredevil movie that has a chance to speak to audiences the way that “Man on Wire” did back in 2008. It’s that cannily crafted and spirited and compelling.

It’s a buddy movie, of sorts, with Kevin Jorgeson signing on to become Tommy’s partner late in the game, and Kevin fighting demons of his own (though maybe less personal ones). The climb is divided into 32 “pitches,” or sections, and the most absurdly challenging of them is a horizontal stretch of rock that barely has ridges a fingertip can grab. Kevin tries it, again and again, dozens of times, and keeps falling in the middle. He can’t seem to nail it. That pitch becomes his fight with the forces, and with himself.

All great athletes represent, on some level, our higher selves: the dream of who we are, or could be. That’s why when someone breaks the world record in the 100-meter dash, it’s on some level everyone’s victory; it’s humanity that triumphs. That’s true, as well, when you watch Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson scale the Dawn Wall. As extraordinarily skilled as they are, the drama is one of daring and devotion. They go up that rock, defying what a human being is supposed to do, because defying those odds is the very essence of what a human being is supposed to do. In “The Dawn Wall,” we get close enough to their achievement to share it, and that’s enough to make anyone in the audience want to shoot the moon.